Dele Giwa: Dreams and Memories

Thursday, 19 October 2023 By Abiodun Kareem Giwa

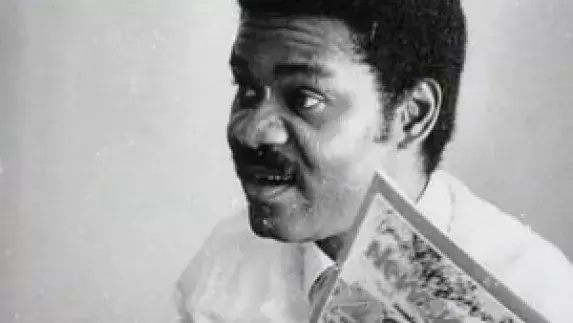

Dele Giwa

Dele Giwa

Dele Giwa, one of Nigeria's most brilliant journalists, was assassinated 37 years ago dramatically with a letter bomb. Recent developments about a young artist, Ilerioluwa Oladimeji Aloba (Mohbad), who died after prolonged harassment from his former boss at a record label, seem to mimic the late reporter's experience and other editors treated shabbily by highhanded media proprietors. It is not a new development. The wand has been long in the country. Media moguls remove editors at whim and dump them, careless of what happens to them when out of favor. It correlates with the boss and the boy philosophy.

The deduction of the boss and the boy matter is from Naira Marley's reference to 27-year-old Mohbad as 'my boy.' You can also deduce this from how some other big guys treat staff. The publisher, Moshood Abiola, removed Dele GIWA from the Sunday Concord editor's seat without any explanation. Of course, big bosses owe no one an explanation. They call the shots, and no one dares question their authority.

Many Nigerians were oblivious of what caused his removal from the editor's position. He suffered soliloquy, moved, and began the Newswstch magazine alongside some of his colleagues. He did not cry out like Mohbad that his boss should be responsible if anything happens to him. The Newswatch was a success story against the Concord publisher's African Concord began to forestall the Newswatch. It was a wonder why the publisher began the African Concord while the Newswatch debuted. It was competitive in outlook, but the Newswatch was unstoppable. Why do the big bosses often try to discourage their boys from outperforming them and putting boobytraps on their path? Have we not gone past the slavery era when traders considered captives lesser human beings and disallowed from thriving?

Unfortunately, Concord Journalists, some of whom knew what happened between the publisher and the editor, kept sealed lips about what led to the editor's travail, unlike Mohbad's cry about his ordeal. Only a few family insiders around Dele knew what transpired between him and the boss. Therefore, when he received a letter bomb two years after leaving the Concord Press ordeal, nothing about his Concord experience came to light. Investigations were on his trial two weeks before his demise.

Who killed Dele GIWA? The media later began chorusing. No journalist dared to tell the truth about what transpired between the journalist and the publisher. Yet, many were information carriers for the publisher about the editor dating the publisher's former girlfriend. The publisher called one of Dele's close colleagues to tell him to remove his hands from the woman. But he sent his colleague back to inform the publisher of the impossibility of his request. The publisher felt insulted.

Consequently, he removed Dele from the editor's post and dumped him on the editorial board. Based on developments shortly before the assassination, Many Nigerians believed the government masterminded the murder. But some sensible observers thought aloud that if it was not the government, the perpetrator must be wealthy enough to acquire a bomb, that no poor fellow could have done it.

Dele and Mohbad's case has shown that a murderer who has made up his mind will find a way to kill whether the victim cries out. Like Mohbad, Dele also cried out after the military intelligence officers interviewed him and accused him of gun-running and a plan to destabilize the country. He confronted his accusers instantly that they wanted him dead. However, no one had asked about the military officers' source of information. Everyone had continued life while Dele's burial plans were afoot.

However, no one dared rush Dele's body into the grave. But there were heated disagreements about his final burial place. Dele's family and Ugbekpe people from his homestead stepped in at this juncture. Close family members said his homestead should be his last home, while others among his friends and well-wishers pressed to have him interned in Lagos. Ugbekpe people supported the return of the body home to enable them to carry out traditional rites towards getting the unknown power who may have masterminded the assassination.

The family expressed a lack of trust in the legal machinery for justice. The villagers supported the family. Traditional rites were held but hidden from public glare except for the masquerades' display that the world saw. Dele was armed to fight and pursue his killers. My mother called from the room where she sat with the women congregation in mourning and introduced me to the traditional rites' undertakers. The traditionalists handed their instruments to me, and I led them to the room where Dele lay in state. They placed the paraphernalia in the coffin before closing it. It was the last rite before the burial. It is what every family that has fallen victim to senseless killing in a lawless State should undertake. It is a fundamental mistake to place a dead body in a grave where men of means can buy justice after death and allow the traducers peace of mind. A representative of the Newspaper Proprietors Association said they would fight in the air and on the ground to ensure justice. Where? I never saw them put up any fight.

Outsiders tried to tamper with my brother's grave after the burial. Still, they were unsuccessful because villagers kept vigil at the grave day and night, warding off intruders. Dele's death crushed many dreams, as often in a star's demise. My pain of loss compelled me to do something to ensure justice to support the villagers' idea. I feel vindicated because, up to this moment, Nigerians are still asking who killed Dele Giwa.

Nigerians with memories will remember the story of a man who wanted to be president and won the election but ended up in the lion's den with a painful death as compensation, and only God knows the cause. It is a tale about Nigeria's powerfully strong men who regard lesser men as boys. They punish their boys for misbehavior and for daring to surpass them. It is what happens in a jungle. When they punish lesser mortals, other higher-ups also prey on them who think of themselves as powerful. It is like a circus.

Dele Giwa's memory remains evergreen in Nigerians' minds as a journalist who refused compromise - a name worthier than gold and diamond. He loathed being anyone's hero but died as one.

The deduction of the boss and the boy matter is from Naira Marley's reference to 27-year-old Mohbad as 'my boy.' You can also deduce this from how some other big guys treat staff. The publisher, Moshood Abiola, removed Dele GIWA from the Sunday Concord editor's seat without any explanation. Of course, big bosses owe no one an explanation. They call the shots, and no one dares question their authority.

Many Nigerians were oblivious of what caused his removal from the editor's position. He suffered soliloquy, moved, and began the Newswstch magazine alongside some of his colleagues. He did not cry out like Mohbad that his boss should be responsible if anything happens to him. The Newswatch was a success story against the Concord publisher's African Concord began to forestall the Newswatch. It was a wonder why the publisher began the African Concord while the Newswatch debuted. It was competitive in outlook, but the Newswatch was unstoppable. Why do the big bosses often try to discourage their boys from outperforming them and putting boobytraps on their path? Have we not gone past the slavery era when traders considered captives lesser human beings and disallowed from thriving?

Unfortunately, Concord Journalists, some of whom knew what happened between the publisher and the editor, kept sealed lips about what led to the editor's travail, unlike Mohbad's cry about his ordeal. Only a few family insiders around Dele knew what transpired between him and the boss. Therefore, when he received a letter bomb two years after leaving the Concord Press ordeal, nothing about his Concord experience came to light. Investigations were on his trial two weeks before his demise.

Who killed Dele GIWA? The media later began chorusing. No journalist dared to tell the truth about what transpired between the journalist and the publisher. Yet, many were information carriers for the publisher about the editor dating the publisher's former girlfriend. The publisher called one of Dele's close colleagues to tell him to remove his hands from the woman. But he sent his colleague back to inform the publisher of the impossibility of his request. The publisher felt insulted.

Consequently, he removed Dele from the editor's post and dumped him on the editorial board. Based on developments shortly before the assassination, Many Nigerians believed the government masterminded the murder. But some sensible observers thought aloud that if it was not the government, the perpetrator must be wealthy enough to acquire a bomb, that no poor fellow could have done it.

Dele and Mohbad's case has shown that a murderer who has made up his mind will find a way to kill whether the victim cries out. Like Mohbad, Dele also cried out after the military intelligence officers interviewed him and accused him of gun-running and a plan to destabilize the country. He confronted his accusers instantly that they wanted him dead. However, no one had asked about the military officers' source of information. Everyone had continued life while Dele's burial plans were afoot.

However, no one dared rush Dele's body into the grave. But there were heated disagreements about his final burial place. Dele's family and Ugbekpe people from his homestead stepped in at this juncture. Close family members said his homestead should be his last home, while others among his friends and well-wishers pressed to have him interned in Lagos. Ugbekpe people supported the return of the body home to enable them to carry out traditional rites towards getting the unknown power who may have masterminded the assassination.

The family expressed a lack of trust in the legal machinery for justice. The villagers supported the family. Traditional rites were held but hidden from public glare except for the masquerades' display that the world saw. Dele was armed to fight and pursue his killers. My mother called from the room where she sat with the women congregation in mourning and introduced me to the traditional rites' undertakers. The traditionalists handed their instruments to me, and I led them to the room where Dele lay in state. They placed the paraphernalia in the coffin before closing it. It was the last rite before the burial. It is what every family that has fallen victim to senseless killing in a lawless State should undertake. It is a fundamental mistake to place a dead body in a grave where men of means can buy justice after death and allow the traducers peace of mind. A representative of the Newspaper Proprietors Association said they would fight in the air and on the ground to ensure justice. Where? I never saw them put up any fight.

Outsiders tried to tamper with my brother's grave after the burial. Still, they were unsuccessful because villagers kept vigil at the grave day and night, warding off intruders. Dele's death crushed many dreams, as often in a star's demise. My pain of loss compelled me to do something to ensure justice to support the villagers' idea. I feel vindicated because, up to this moment, Nigerians are still asking who killed Dele Giwa.

Nigerians with memories will remember the story of a man who wanted to be president and won the election but ended up in the lion's den with a painful death as compensation, and only God knows the cause. It is a tale about Nigeria's powerfully strong men who regard lesser men as boys. They punish their boys for misbehavior and for daring to surpass them. It is what happens in a jungle. When they punish lesser mortals, other higher-ups also prey on them who think of themselves as powerful. It is like a circus.

Dele Giwa's memory remains evergreen in Nigerians' minds as a journalist who refused compromise - a name worthier than gold and diamond. He loathed being anyone's hero but died as one.

Widget is loading comments...