New book, unresolved murders and media freedom

December 17 2014 By Abiodun Giwa

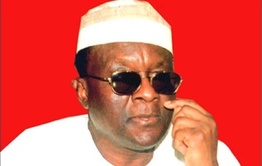

(Courtesy:www.adibba.com)

(Courtesy:www.adibba.com)

Journalists are beheaded; they are bombed and shot to death. They are arrested and hounded into jail, and have become targets for combatants in warfare, who seek to settle scores, based on political and ideological differences. And there are many unresolved journalists' assassinations around the world, recalling a new book on the assassination of a Nigerian journalist - Dele Giwa - with a bomb in his home, on October 19, 1986.

Dele Giwa's younger brother reports in detail, based on a study of the new book, the study of a review by an independent writer, interviews on the new book and the state of media freedom around the world , amid seeming new dangers journalists face on the job.

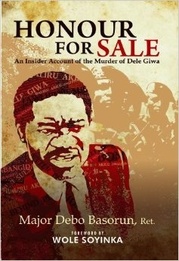

"Honour for Sale", authored by Debo Basorun, formerly of the Nigerian Army, has become controversial like the assassination case the book sets to resolve, believably unresolved for twenty eight years, involving the country's former dictator, Ibrahim Babangida, and two of the country's military intelligence officers.

"The book unravels NOTHING. The book establishes possible motives behind the killing. The 'boldness' was used in the review because nobody has ever come out in a book form like this, to talk publicly about these possible motives," Moshood Abolore Folorunsho of Educare Trust, who reviewed the book, said in an interview. He cited journalists' delicate work of exposing corrupt practices and human rights' abuses, as what the author wrote was behind the journalist's murder.

"I am not aware that one Mr. Abolore reviewed the book. The latest review done to the book was by Channels TV Book Club, which attracted a torrent of rave positive reactions from all over the globe, the latest being a request from a scholar in Australia, for a copy. There is no part of the book in which I claimed Dele Giwa was a member of any committee of government," the author said in an interview. "As reflected in the book, I was a member of that committee. I am the person who may have unknowingly participated in a drug running business in the course of carrying out military directives."

One area is the author's disclosure about government's confusion as to the source of Dele's troubles, he wrote led to government’s instruction for him to follow the Newswatch executives around to gather information over suspicion that the company's executives may have killed their colleague over the company's ownership. When contacted, Soji Akinrinade, former senior associate editor on the Newswatch magazine, when Dele was editor-in-chief, and later a director after Dele's assassination, said, he had not read "Honour for Sale", and that he could not vouch for the author.

One reader, a member of Giwa's family, sought anonymity about her view of the book, said that the book’s description as "an insider’s account of Dele Giwa’s murder," the use of Dele's photograph and description of the assassination as outrightly unresolved are ploys to use the controversy over the investigation into the assassination sell a book. According to her, issues about the assassination were only mentioned in passing throughout the book.

Abolore confirmed the family member's position in his review that the first 10 chapters of the book read much like the author's autobiography.

* * *

People ask whether it is true or false that Okon is alive. If she is alive, has anyone seen her since? And if she has died, does anyone know about her death and time of her death, aside from the government’s announcement in 1985?

Dele Giwa's younger brother reports in detail, based on a study of the new book, the study of a review by an independent writer, interviews on the new book and the state of media freedom around the world , amid seeming new dangers journalists face on the job.

"Honour for Sale", authored by Debo Basorun, formerly of the Nigerian Army, has become controversial like the assassination case the book sets to resolve, believably unresolved for twenty eight years, involving the country's former dictator, Ibrahim Babangida, and two of the country's military intelligence officers.

"The book unravels NOTHING. The book establishes possible motives behind the killing. The 'boldness' was used in the review because nobody has ever come out in a book form like this, to talk publicly about these possible motives," Moshood Abolore Folorunsho of Educare Trust, who reviewed the book, said in an interview. He cited journalists' delicate work of exposing corrupt practices and human rights' abuses, as what the author wrote was behind the journalist's murder.

"I am not aware that one Mr. Abolore reviewed the book. The latest review done to the book was by Channels TV Book Club, which attracted a torrent of rave positive reactions from all over the globe, the latest being a request from a scholar in Australia, for a copy. There is no part of the book in which I claimed Dele Giwa was a member of any committee of government," the author said in an interview. "As reflected in the book, I was a member of that committee. I am the person who may have unknowingly participated in a drug running business in the course of carrying out military directives."

One area is the author's disclosure about government's confusion as to the source of Dele's troubles, he wrote led to government’s instruction for him to follow the Newswatch executives around to gather information over suspicion that the company's executives may have killed their colleague over the company's ownership. When contacted, Soji Akinrinade, former senior associate editor on the Newswatch magazine, when Dele was editor-in-chief, and later a director after Dele's assassination, said, he had not read "Honour for Sale", and that he could not vouch for the author.

One reader, a member of Giwa's family, sought anonymity about her view of the book, said that the book’s description as "an insider’s account of Dele Giwa’s murder," the use of Dele's photograph and description of the assassination as outrightly unresolved are ploys to use the controversy over the investigation into the assassination sell a book. According to her, issues about the assassination were only mentioned in passing throughout the book.

Abolore confirmed the family member's position in his review that the first 10 chapters of the book read much like the author's autobiography.

* * *

People ask whether it is true or false that Okon is alive. If she is alive, has anyone seen her since? And if she has died, does anyone know about her death and time of her death, aside from the government’s announcement in 1985?

However, the book has raised an important question whether the journalist's assassination was connected to military officers' involvement in drug business, as claimed by Chief Gani Fawehinmi - the lawyer who investigated the assassination - and who said that Dele was assassinated over a meeting with Gloria Okon - a drug courier, arrested, but whom the government had said previously died in custody in 1985. The lawyer had said Dele had a story he wanted published on his meeting with the drug courier. The author mentioned some senior military officers' involvement in drug businesses, but no mention of Okon and Dele in relation to the assassination.

The Newswatch Communications, at the time the lawyer made his statement following the assassination, had rejected the lawyer’s claim about an alleged meeting or any story in the making about the alleged an meeting between Dele and Okon.

The author relied on his own reactions, but mostly on the reflexes, moods and reactions of the head of state against his own request that government should felicitate with the magazine when Dele's deputy, Ray Ekpu, won the "International Editor of the Year" award, shortly after the assassination, to reach conclusions that the government was working against the magazine. He also could not stomach instructions for him to monitor Newswatch executives for information about the likelihood of their involvement in Dele's assassination for business reasons.

Rather than the author's reliance on the mundane, readers interviewed at random expected either acceptance or rejection of earlier known accusation from investigation into the assassination. People ask whether it is true or false that Okon is alive. If she is alive, has anyone seen her since? And if she has died, does anyone know about her death and time, aside from the government’s announcement in 1985?

The Newswatch Communications, at the time the lawyer made his statement following the assassination, had rejected the lawyer’s claim about an alleged meeting or any story in the making about the alleged an meeting between Dele and Okon.

The author relied on his own reactions, but mostly on the reflexes, moods and reactions of the head of state against his own request that government should felicitate with the magazine when Dele's deputy, Ray Ekpu, won the "International Editor of the Year" award, shortly after the assassination, to reach conclusions that the government was working against the magazine. He also could not stomach instructions for him to monitor Newswatch executives for information about the likelihood of their involvement in Dele's assassination for business reasons.

Rather than the author's reliance on the mundane, readers interviewed at random expected either acceptance or rejection of earlier known accusation from investigation into the assassination. People ask whether it is true or false that Okon is alive. If she is alive, has anyone seen her since? And if she has died, does anyone know about her death and time, aside from the government’s announcement in 1985?

Another area some members of the public seek clarification is about the involvement of the country's president and intelligence officers. Information that the murder envelope with the president’s name affixed as the sender, and that it was graced with the country’s coat of arms, had long circulated. Seeking information about police procedure in an investigation of the type led to New York Police officer, Wayne Magan, who noted in an interview, "It was possible and impossible to accept that the president and intelligence officers’ could approve the president’s name as sender, and the use of an envelope with the country's coat of arms, unless such a development can be scientifically disputed." Officer Magan added that if anyone outside the government had affixed the president’s name along with the coat of arms, it could be treason, and as such, it could create upheaval against the government.

Public reaction in Nigeria at the time of the assassination supports Magan’s point. President Ibrahim Babangida felt backlash from the assassination and later, Gideon Orkar's coup led to his flight from Lagos to Abuja, as nation's official seat of government.

But doubting the possibility that a president and intelligence officers could approve such a dastardly operation reminiscent of a coup against itself, a respondent who spoke off the record said, "It is bizarre to think that a president and his intelligence officers would approve a president’s name as a sender on a murder envelope to a journalist. The natural thing is for people committing atrocities to cover their tracks. It is possible for the murderers to have used the president’s name on the murder envelope to divert attention and create a problem for the government."

While many observers eyed the government as the culprit, others pointed the finger at another journalist, Kayode Soyinka, who was in the library with Dele on the day of the assassination over a suspicion about the remote control to the bomb, and that the bomb may have been planted under the journalist's seat. Bugging and bugging devices were found in bathrooms, both in Dele and his deputy's home, and which observers said only an insider was capable of undertaking. Questions about Soyinka's mission in Nigeria had been answered by the Newswatch executives that as the magazine correspondent in London, Soyinka had the right to visit Nigeria.

But on October 17, 1986, three days to the assassination, Dele's driver told this reporter, "Uncle, I have to go quickly to the airport to bring Soyinka, because editor is angry. He said he does not know why Soyinka is coming to Nigeria." And yet Soyinka was a guest in Dele's house from that date and until after the assassination.

Mostly absent from Basorun's account were Dele's years as Sunday editor in the Concord Press spanning 1981 - 1984, where he practiced intense investigative journalism, which endeared him to the Nigerian public as a thorn in corrupt officials' sides. It was why majority of Nigerians felt and said only the government or wealthy individuals, capable of acquiring a bomb could have killed him.

Other theories abound. Basorun has merely added another dimension that the then head of the State Security Service, (SSS), Aliyu Gusau, may have been involved in the planning of the assassination without giving details. Available information that emerged a week before the military intelligence invitation was issued to Dele for interrogation, showed that Gusau was first to alert the journalist through a night phone call, informing him that someone unnamed had given deadly information to the government against him (Dele), and that Dele should make contacts to void the unnamed informant’s intention, contradicts Basorun's opinion.

Public reaction in Nigeria at the time of the assassination supports Magan’s point. President Ibrahim Babangida felt backlash from the assassination and later, Gideon Orkar's coup led to his flight from Lagos to Abuja, as nation's official seat of government.

But doubting the possibility that a president and intelligence officers could approve such a dastardly operation reminiscent of a coup against itself, a respondent who spoke off the record said, "It is bizarre to think that a president and his intelligence officers would approve a president’s name as a sender on a murder envelope to a journalist. The natural thing is for people committing atrocities to cover their tracks. It is possible for the murderers to have used the president’s name on the murder envelope to divert attention and create a problem for the government."

While many observers eyed the government as the culprit, others pointed the finger at another journalist, Kayode Soyinka, who was in the library with Dele on the day of the assassination over a suspicion about the remote control to the bomb, and that the bomb may have been planted under the journalist's seat. Bugging and bugging devices were found in bathrooms, both in Dele and his deputy's home, and which observers said only an insider was capable of undertaking. Questions about Soyinka's mission in Nigeria had been answered by the Newswatch executives that as the magazine correspondent in London, Soyinka had the right to visit Nigeria.

But on October 17, 1986, three days to the assassination, Dele's driver told this reporter, "Uncle, I have to go quickly to the airport to bring Soyinka, because editor is angry. He said he does not know why Soyinka is coming to Nigeria." And yet Soyinka was a guest in Dele's house from that date and until after the assassination.

Mostly absent from Basorun's account were Dele's years as Sunday editor in the Concord Press spanning 1981 - 1984, where he practiced intense investigative journalism, which endeared him to the Nigerian public as a thorn in corrupt officials' sides. It was why majority of Nigerians felt and said only the government or wealthy individuals, capable of acquiring a bomb could have killed him.

Other theories abound. Basorun has merely added another dimension that the then head of the State Security Service, (SSS), Aliyu Gusau, may have been involved in the planning of the assassination without giving details. Available information that emerged a week before the military intelligence invitation was issued to Dele for interrogation, showed that Gusau was first to alert the journalist through a night phone call, informing him that someone unnamed had given deadly information to the government against him (Dele), and that Dele should make contacts to void the unnamed informant’s intention, contradicts Basorun's opinion.

Another unresolved theory surrounds the damaged relationship between Concord Press publisher Moshood Abiola, and Dele, over a female reporter who later became Dele's wife, but whom Abiola said belonged to him and he asked Dele to keep his hands off. But, Dele had told Abiola through the same person Abiola sent to him that he was not taught in school that when a woman fell in love with him, he should reject her because his publisher had expressed interest. It was the reason for Abiola’s removal of Dele as Sunday editor of his newspapers and the end of amity between them.

The public knew there was a problem between the Abiola and Dele - one of his finest editors, but few knew the cause of what later became a reason for the duo's lifetime of discord and enmity. Some editors who knew about the development kept sealed lips. Abiola attempted a reconciliation effort with Dele's family by reaching out to help after the assassination, but he was cut short by his own trouble with the same government over his victory in the 1993 presidential polls; the government’s annulment of the election, his struggle for validation of the election, imprisonment and consequent death in jail.

Many Nigerians considered the annulment of Abiola’s election as a coup against the publisher, and they asked about what Abiola may have done that warranted such a reprisal from Babangida, considered his best friend, and also the head of state, whose 1985 coup that paved the way for his emergence as a military president was reliably bankrolled by Abiola. Nigerians consider both men as coup specialists.

The trouble between the publisher and his editor was silent, because newspaper reports and the Nigeria Police investigations were primarily focused on a short period of two weeks from the encounter between military intelligence officers and Dele, over allegations that he planned to ferment a socialist revolution and that he was into gun running, and all which Dele said were news to him.

Abubakar Tsav, a former commissioner of police in Lagos State, who investigated the case, asked to be allowed to interrogate military intelligence officers, but his request was turned by the authorities.

However, in1999, a new civilian government established a panel of investigation into all the wrongdoings in the country, including miscarriage of justice in the1993 presidential election, won by the publisher.

The reconciliation panel, led by Justice Chukwudifu Oputa, recommended that the military government in power when the journalist was assassinated could not claim ignorance about the assassination, and asked the new civilian government to address the issue. But nothing was done by the civilian government, itself an apron of retired military government. Deadlock in court hearings and later award of costs, against the investigating lawyer in favor of intelligence officers, meant Dele's killers were yet to be found.

But some people wonder, whether, indeed the assassination case has yet to be resolved. They talk about a ritual performed on Dele's body before burial, and ask about the effort to resolve a debacle arising from a lack of respect for rule of law, an attempt to cover up and apparent resort to jungle justice against one of their own. They point to the loggerheads over an election between Babangida and Abiola over an election Abiola won but later annulled, and they ask about what may have caused the struggle and consequent rubbishing of Abiola by the military. Amid the scenario is the debate about media freedom and new dangers journalists face on the job.

Speaking on the conflict between the media and people in public authority and its effect on world press freedom in relation to development in Nigeria, a United States’ former ambassador to Nigeria, John Campbell, said, "The cause of the conflict between people in public authority and the media is because people in public authority don’t like criticism, and that it is why the media requires a strong constitutional protection." He said the media in Nigeria is legally free, but that it is also subject to intimidation from time to time.

"Whether a press is free or not depends on time and place," Professor John Richard of Columbia University said. He mentioned times journalists have been subject to violence, which he said was certain true of the US in the 19th century and also true of Europe and other parts of the world, a reminder of Campbell’s statement on the universal conflict between the media and people in public authority; the struggle between printers and public authority in Britain, following the invention of the printing press.

“The liberty of the press is indeed essential to the nature of a free state; but this consists in laying no previous restraint upon publications; and not in freedom from censure on criminal matter when published. Every freeman has an undoubted right to lay what sentiments he pleases before the public, and that to forbid this is to destroy the freedom of the press, but that if anyone publishes what is improper, mischievous or illegal, such a writer must face the consequence," Sir William Blackstone - "The Law of Journalism and Mass Communication" by Robert Trager, Joseph Russomammo and Susan Dente Ross (55).

In a seeming reference to Sir Blackstone’s statement, Professor Richard talked about laws and conventions guiding operations of the press from country to country. "The question of press freedom really is a matter of law. In certain countries, there are institutional safeguards to protect journalists from some kind of state’s surveillance and harassment." He frowns on journalists being subject of constraints and spoke of the need for new journalists to understand the laws and conventions of the country in which they are working.

"Whether a press is free or not depends on time and place," Professor John Richard of Columbia University said. He mentioned times journalists have been subject to violence, which he said was certain true of the US in the 19th century and also true of Europe and other parts of the world, a reminder of Campbell’s statement on the universal conflict between the media and people in public authority; the struggle between printers and public authority in Britain, following the invention of the printing press.

“The liberty of the press is indeed essential to the nature of a free state; but this consists in laying no previous restraint upon publications; and not in freedom from censure on criminal matter when published. Every freeman has an undoubted right to lay what sentiments he pleases before the public, and that to forbid this is to destroy the freedom of the press, but that if anyone publishes what is improper, mischievous or illegal, such a writer must face the consequence," Sir William Blackstone - "The Law of Journalism and Mass Communication" by Robert Trager, Joseph Russomammo and Susan Dente Ross (55).

In a seeming reference to Sir Blackstone’s statement, Professor Richard talked about laws and conventions guiding operations of the press from country to country. "The question of press freedom really is a matter of law. In certain countries, there are institutional safeguards to protect journalists from some kind of state’s surveillance and harassment." He frowns on journalists being subject of constraints and spoke of the need for new journalists to understand the laws and conventions of the country in which they are working.

Video:Professor John Richard of Columbia University speaks on press freedom and the law |

Video: John O'Connor of Long Island Herald speaks on effect of internet on press freedom |

An index (below) by the Committee for the protection of Journalists, CPJ, shows that unresolved journalists’ assassinations are on the rise. Elizabeth Witchel writing in a 2014 CPJ publication, reveals that fresh violence and failure to prosecute old cases have become a bane to media freedom.

May 3 every year is World Press Freedom day. Reporters without Borders’ statement marking the day in 2014 said that the Press Freedom is consistently under attack.

"I agree that journalism is a dangerous profession," Sonny Albarado, Society for Professional Journalists' former chairman submitted. "The US journalists’ enjoy comfort and the existence of strong support networks of employers other than journalists’ organization such as SPJ. I will recommend same for journalists in other countries to cushion against unjust imprisonment and unresolved killings." Long Island Herald's executive editor, John O'Connor, speaks on the positive role of the internet.

May 3 every year is World Press Freedom day. Reporters without Borders’ statement marking the day in 2014 said that the Press Freedom is consistently under attack.

"I agree that journalism is a dangerous profession," Sonny Albarado, Society for Professional Journalists' former chairman submitted. "The US journalists’ enjoy comfort and the existence of strong support networks of employers other than journalists’ organization such as SPJ. I will recommend same for journalists in other countries to cushion against unjust imprisonment and unresolved killings." Long Island Herald's executive editor, John O'Connor, speaks on the positive role of the internet.

Click to set custom HTML

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Campbell and Richard agree on the need for journalists to abide by the ethics of the profession. Campbell spoke specifically of countries like Nigeria where he said journalists need to improve on investigation and verification, and where he said some people buy media coverage.

Richard said in some parts of the world, journalists are poorly paid, some accept bribes and that in others they don’t. He said it is important for journalists to tell the truth; that this presents a difficult challenge in different countries, and that it depends very much upon circumstances.

The relationship between media owners and journalists denoting ''the piper dictating the tune culture'', based on public perception that some journalists are appendages to media owners’ politics and ideology, and whether the people in public authority constitute more problems to media freedom than media owners, Jennifer Dunham of the Freedom House said, "Both represent a potential threat to press freedom. The extent to which one is worse than the other varies from country to country. In more repressive media environments, the extent media owners and governments undermine media freedom is closely linked."

Reports from Nigeria indicate the situation in the country has not changed about killing of journalists and self-censorship. A CPJ's figure shows that of the 1080 journalists killed since 1992 worldwide, 19 are from Nigeria. Motives behind nine of the 19 killings confirmed, and remaining 10 unconfirmed - like that of Giwa before them. Emmanuel Ojukwu, Nigeria Police public relations officer said that Giwa's assassination case is still open, and that the kind of case rarely closed.

Aside from cases of journalists' unresolved murders around the world, journalism from inception has posed a challenge to people who have truth to hide, and that has put journalists on danger spots of unwarranted imprisonments. Deaths by bomb, beheadings and commando-style killings, are new dangers journalists face on the job.

Richard said in some parts of the world, journalists are poorly paid, some accept bribes and that in others they don’t. He said it is important for journalists to tell the truth; that this presents a difficult challenge in different countries, and that it depends very much upon circumstances.

The relationship between media owners and journalists denoting ''the piper dictating the tune culture'', based on public perception that some journalists are appendages to media owners’ politics and ideology, and whether the people in public authority constitute more problems to media freedom than media owners, Jennifer Dunham of the Freedom House said, "Both represent a potential threat to press freedom. The extent to which one is worse than the other varies from country to country. In more repressive media environments, the extent media owners and governments undermine media freedom is closely linked."

Reports from Nigeria indicate the situation in the country has not changed about killing of journalists and self-censorship. A CPJ's figure shows that of the 1080 journalists killed since 1992 worldwide, 19 are from Nigeria. Motives behind nine of the 19 killings confirmed, and remaining 10 unconfirmed - like that of Giwa before them. Emmanuel Ojukwu, Nigeria Police public relations officer said that Giwa's assassination case is still open, and that the kind of case rarely closed.

Aside from cases of journalists' unresolved murders around the world, journalism from inception has posed a challenge to people who have truth to hide, and that has put journalists on danger spots of unwarranted imprisonments. Deaths by bomb, beheadings and commando-style killings, are new dangers journalists face on the job.

Widget is loading comments...